INEQUALITY IN EUROPE: UNEQUAL TRENDS

87

Policy against inequality

In view of these findings, any policy for more

equality in Europe faces various challenges: while

Central and Eastern Europe should continue to

grow “just like that”, growth needs to be stimu-

lated anew in Southern Europe. The most signifi-

cant dangers threaten the states from inside

through the deterioration of the regional, per-

sonal and functional income distribution.

Before diminishing inequality between the

states, the poorest EU Member States need, first

and foremost, to show a high and stable

growth. Since Ireland’s accession in the 70s, the

EU has been creating a regional and structural

policy to this aim, which adds up to approxi-

mately 40 % of the EU budget which, however,

measures less than 1 % of the EU GDP. The ef-

fects of this policy are controversial. Usually,

poor regions have scarcely caught up inside

their countries. Within the EU as a whole, re-

gions in poor countries have taken advantage of

their catch-up growth though. The Italian

Mezzogiorno

or Eastern Germany are a testi-

mony to the limited effectiveness of massive

European and national programmes. The Irish

model (cf. above) can’t be used as an example

for the whole European periphery, since the di-

mensions needed to this extent, that is, foreign

direct investments per inhabitant and profits

transferred to avoid taxes, are completely unre-

alistic.

Instability in the supply of capital has proven

to be the most significant risk for the catch-up

process, as seen in the financial crisis as well as

globally before in the Asian crisis. On the do-

mestic side, it’s possible to take preventive

measures in the framework of a clever financial

market policy that imposes limits to speculative

investments and indebtedness in foreign curren-

cies. High current account deficits should give

way to restricting the credit expansion, examin-

ing the wage development and to taking meas-

ures to increase the structural competitiveness

through better training and innovation.

Inversely, surplus countries should reinforce

their domestic demand. The EU should entrust

the periphery’s supply of capital less to the mar-

kets and politically manage flows, i.e. through

investment programmes. Europe needs a vision-

ary industrial policy (Aiginger 2015).

8

The EU

should develop towards a transfer union with a

greater emphasis on the EU budget and with an

European insurance against unemployment.

Southern Europe must change its economic

policy priorities: more employment, innovation

and a modernisation of the productive structure

instead of budget consolidation (Dauderstädt

2016). The Euro area must steer its savings to-

wards its own welfare increasing projects and,

8

Aiginger Karl: Industriepolitik als Motor einer Qual-

itätsstrategie mit gesellschaftlicher Perspektive. In:

WSI-

Mitteilungen

7/2015, 507-15.

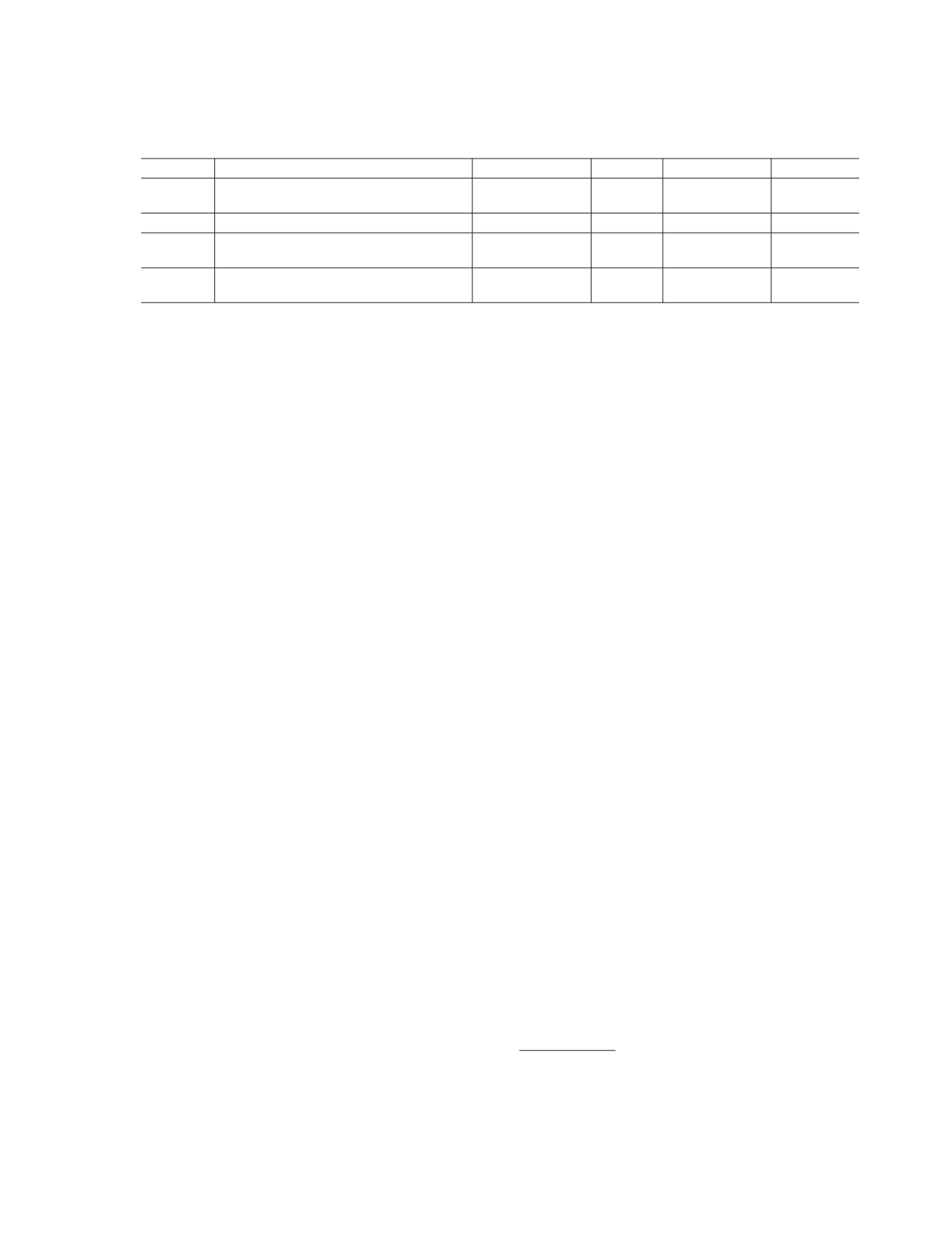

Table 10.

The different dimensions of the Europe-wide inequality (quintile share ratio)

Level

Indicator (S80/S20)

Earliest

Year

Last

Year

1.

Neglecting inequality within countries

2.6 (PPP)

5.4 (

€

)

2005

2.0 (PPP)

3.7 (

€

)

2014

2.

Neglecting inequality within regions

4 (PPP)

2000

2.8 (PPP)

2011

3.

Neglecting inequality between

countries (Eurostat value)

5 (PPP)

2005

5.2 (PPP)

2014

4.

Considering both inequalities

7 (PPP)

11 (

€

)

2007

6.2 (PPP)

9.6 (

€

)

2013